In this digital age of surveillance and technology, the law has plenty to aid in bringing criminals, murderers and rapists to justice.

So it might come as some surprise to know that when all else fails, the expertise of a small, soft-spoken Welsh woman with a passion for all things plants and pollen is who they often turn to when a case is particularly hard to solve.

Professor Patricia Wiltshire, 74, is the UK’s leading forensic ecologist. Her expert analysis has been called upon for more than 250 criminal cases, including some of the most high-profile crimes of the past 25 years.

Born in South Wales, Wiltshire’s childhood was wrought with illness—she endured repeated chest infections that often left her too ill to attend school and suffered a horrifying accident in which she was burned with hot oil.

“When I was seven, I decided to scare my mother by jumping out on her and shouting ‘boo,’ not realising she was carrying a pan of hot chip fat.

“I got badly burnt and ended up covered in bandages for two years.

“I also suffered from pneumonia, measles, whooping cough and bronchitis, which left me with a chronic cough problem,” Wiltshire told the BBC.

So, Wiltshire turned to a set of encyclopedias for her education and taught herself “everything from music to knitting and nature.”

When she was eight, her parents sent her to stay with her beloved grandmother, Vera May, in Rhyl, on the North Wales coast, hoping that the fresh sea air would help restore her lungs.

“She knew all about the natural world: which plants were edible and which were poisonous. She showed me the hedgerow plants and berries that provided a natural larder. For two wonderful years, she taught me all the things she knew,” Wiltshire recounted in an Essential Surrey interview.

“I found so many tiny, obscure foreign things between the chopped-off grass. I realised that the soil was infinitely variable over short distances and home to so many little things with legs. This is where it all comes from—this fascination, not only with nature but with the stuff beneath the surface.”

At the age of 17, Wiltshire moved to London and began a job in the civil service. For the next decade, she trained as a medical laboratory technician at Charing Cross Hospital, learning histology (the microscopy study of tissue), bacteriology and biochemistry.

She then went on to get a first in Botany and Ecology at King’s College London, where she became a lecturer, before moving to University College (UCL). There she got involved in palynological research—the study of pollen, plant spores, fungal spores and any microscopic entity in a sample.

Pollen and spores can last for millions of years if conditions are right, even on surface soil and vegetation.

“People may not realise it, but pollen and spores can tell us stuff that DNA and fingerprints simply can’t.”

“Pollen isn’t easily washed away and it stays on people’s clothes and shoes. If you walk on soil or vegetation, you inevitably pick it up.”

Source: BBC Wales

So, Wiltshire began specialising in archaeological sites—taking soil samples and recreating the environment in and around Roman-era sites, such as Hadrian’s Wall in northern England and Pompeii in Italy.

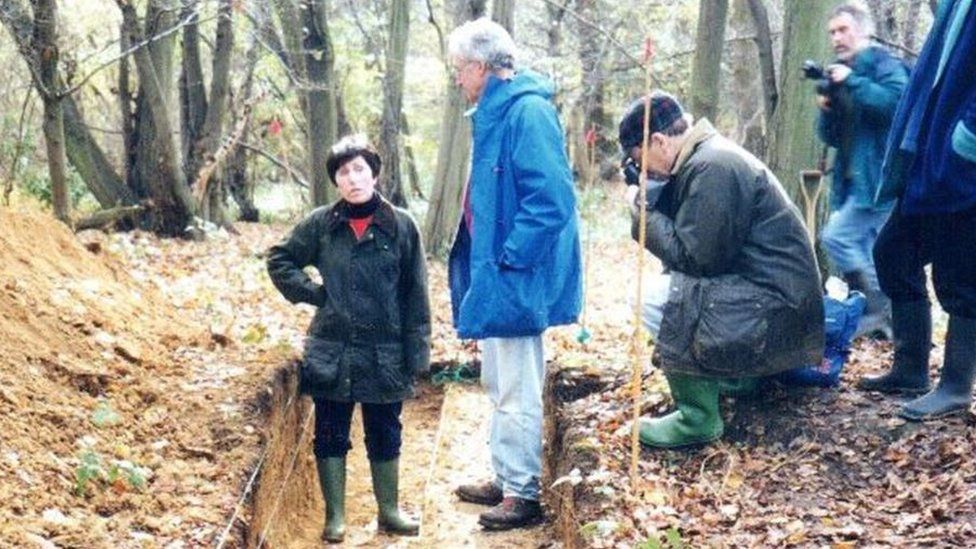

Prof Patricia Wiltshire giving advice to archaeologists in the early 1990s

Who you gonna call?

Then, in 1994, when she was in her fifties, Prof Pat Wiltshire received a phone call that would change the trajectory of her life and career forever.

It was the Hertfordshire police asking if she could help with a murder.

The detective on the end of the line explained that they were investigating a Triad gang murder. They had a charred body in a ditch, a car, tyre marks in an adjacent field and a few suspects. What they didn’t have was proof that the car had been used to drive the victim through the field where his burned body had been found.

The detective in charge then had a brainwave: Could there be maize pollen in the field that had stuck to the wheels?

Prof Wiltshire said:

“I’d never done anything like it before, but I analysed everything in the car and found pollen from the pedals and footwell matched that of an agricultural field edge.

“When police took me to the crime scene, I was able to identify the exact spot where the body had been dumped from the types of flowers in that section of the hedge.

“It was a eureka moment for me because I didn’t think it would be that specific.”

The case was a catalyst and Wiltshire began to work on more and more cases across the UK and Wales.

In 2002, she helped police gather critical evidence that helped solve the case of murdered Cambridgeshire schoolgirls, Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman. Police had discovered their bodies in a ditch but wanted to establish the approach path their killer had used. Wiltshire was able to do this by analysing the re-growth of trampled plants leading to the crime scene. Police then conducted a detailed search of her route and found one of Jessica’s hairs on a twig.

Wiltshire then gave evidence in the infamous trial of Ian Huntley who was convicted of murdering the two ten-year-old girls. Just an hour after she’d given evidence at the Old Bailey, Huntley’s barrister stood up and announced that his client wished to plead guilty.

Other high profile cases she has been involved with include the child murders of Milly Dowler and Sarah Payne, and five women murdered by a serial killer in Ipswich in 2006.

“A Messy Life”

Wiltshire says that “life has happened to me,” and jokes that “life has been a mess.”

Now in her 70s, and married to one of the world’s leading fungi experts, Prof David Hawksworth, Patricia Wiltshire’s path to becoming a renowned forensic ecologist has been exactly that… a mess.

“If I hadn’t had all the experiences I had—in hospitals, laboratories, palynology, bacteriology all those weird and wonderful things… all that ecological fieldwork, I couldn’t do what I do now,” the badass eco-crime solver explained in a Life Scientific interview in her soft Welsh accent.

“It required all of those weird things. That messy background to be able to do this.”

There is a lesson in there, and Wiltshire says on top needing the combination of her varied skills, laboratory experience and microscopic knowledge of pollen, her other most important tool has been a curiosity to try anything.

In an impossibly positive tone for a woman who has seen so much destruction and suffered so much herself, she reeled off some of her mottos: “Have a go, just have a go. Suck it and see. See if it works. Nothing ventured nothing gained.”

In July this year, Wiltshire published her memoir, Traces—a unique book on life, death, and one’s indelible link with nature.